Feeling more than a little intrigued by where George’s circumlocutions were leading, Konrad decided to stick with the conversation.

“George, this is very interesting. But where did all this stuff about the efficiency of functionaries and computers come from?” asked the intern.

“Oh, it’s come to me over the years,” replied George, eager to press on and provide the answer. “Though, certainly, something rubbed off from Parkinson himself!”

Konrad smiled respectfully in order to make way for George to continue.

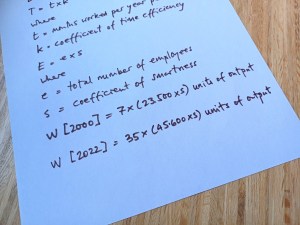

“So, let’s start with ‘capital T’, Effective time available. ‘Little t, the number of months worked per year per employee has not changed much, and equals about 7 working months over a whole year. Then ‘Little t is multiplied by ‘little k’, the Coefficient of time efficiency, which I reckon is about one fifth compared to what it was 30 years ago.”

Konrad’s hand twitched, tentatively.

“But what brought you to a figure of one fifth?” he asked.

“Nothing, really. It’s just a guess. But I reckon the truth must be somewhere between nought and one tenth, so one fifth seems a good compromise,” George chimed.

“So, if we divide seven by one-fifth, we get thirty-five, as the number of effective working months of an average functionary in 2025,” George rambled on as he wrote down the sum.

“But there you have it, George. That’s why colleagues think the AI tool is going to cause job losses! One person now with a computer replaces five from 30 years ago!” interjected Konrad, the only person from the original coffee conversation who could remember what the starting point had been.

“Yes, yes. I don’t deny that time efficiency is a big part of it. But it’s only one factor in the equation. And this is where the data come in useful,” said George calmly.

George took his phone and tapped in a Google search: ‘ERA evolution in staff numbers’.

In a flash, a graph appeared.

“Here, the graph gives the number of fixed and temporary staff from 2000 to 2022. That’s near enough. Take note of these numbers,” George said, passing the pen to Konrad.

“Year 2000, statutory staff, eighteen thousand, temporary staff five thousand, five-and-a-half thousand, more or less,” George stuttered, squinting to estimate the figures approximately from the graph. “In any case, let’s say, twenty-three thousand five hundred as the total number, back then, of employees in the ERA”.

Konrad noted the figures down on the right-hand side of the equation.

“Now, year 2022, statutory staff, we don’t see much change there, about seventeen thousand six hundred. But temporary staff, they’re up to twenty-eight thousand. Look, half of them in the ERA, and half in the new agencies. So, the total for 2022 is about seventeen thousand six hundred plus twenty-eight thousand, which gives a total of forty-five thousand six hundred.”

Konrad’s eyes widened with surprise.

“Did you know all along that staff numbers had doubled?”, asked Konrad.

“Well, I had mentioned it earlier”, said George “but nobody was ready to believe me.”

He paused, this time to calm himself. “There are far more people working in agencies now than there were thirty years ago.”

“Have you got those numbers down?” asked George, as Konrad rewrote the equation.

Konrad was really getting interested now.

“Has there been any change in the Coefficient of smartness over that period?” Konrad enquired, his training in quantitative political science starting to show how well equipped he was for having such an arcane discussion as the one George was leading him into.

“Aha! Now that’s an interesting question!” retorted George. “And I don’t think I can give you a straight the answer, I’m afraid.”

George paused.

“For the sake of simplicity,” he rejoined, “let’s assume that the youngsters nowadays are just as bright as the old foxes from last century!”

Konrad smiled again, indulgently.

“I don’t doubt the new generation are much quicker,” continued George. “But I worked with quite a few of the old timers, and I can assure you they were very shrewd operators”.

George winked again at Konrad, who by now had decided he was prepared to tolerate George’s sense of humour and somewhat eccentric manner. He appreciated George’s enthusiasm and whacky ideas on such off-beat matters.

“OK, let’s resolve the equations,” pronounced George. “Get your calculator out.” Konrad swiped his phone and began to type in the figures.

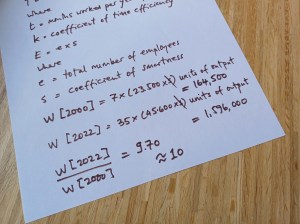

“We can let ‘little s’ drop because we are taking it as a constant. That means that the workload ‘W year two thousand’ equals seven times twenty-three thousand five hundred, which gives one hundred and sixty-four thousand five hundred,” called out Konrad while George held the pen.

“And ‘W year two thousand twenty-two’ equals thirty-five times forty-five thousand six hundred, which gives one million five hundred and ninety-six thousand.”

“Great,” said George. “Now divide that last number by one hundred and sixty-four thousand five hundred, to give us the ratio of the change in workload over twenty years.”

Konrad tapped in the necessary figures.

“Nine point seven zero,” Konrad replied.

“There you go,” George quickly came back. “A ten-fold increase in workload over 22 years! Seems about right to me.”

Konrad looked a little taken aback.

“You see why I told you they were missing the best bit!” chuntered George, showing the first small sign of self-satisfaction.

Konrad stopped to think.

“So, extra work demand has outstripped the increase in efficiency from computers? Is that what this is saying?” said Konrad, struggling to formulate his thoughts as a question.

“Yep,” replied George. “Past experience shows that, alongside the introduction of computers, our political masters have kept expecting us to produce more and better outputs. So computers haven’t cost any jobs for functionaries! Quite the contrary!” announced George, with a quiet air of triumph.

“On a good day, I can even lull myself into believing that computers and AI are the functionary’s best friend. They allow us to do more and to do everything better, which pleases our customers, the bosses, because ‘Quality in Quantity’ is exactly what they expect from us.”

[to be continued]