Image courtesy of Truus, Bob & Jan too!

Even so, it wasn’t just a few brushes with some prickly characters, in his first weeks at the European Regulatory Authority, that put George on edge.

Before he had opportunity to meet other colleagues, who he would later come to consider as friends, and had the chance to appreciate aspects of the ways of working, which he would in time find to be part of parcel of the robustness of the EU institutions, George had become quite alarmed by the archaic nature of some of the working practices he encountered.

What’s more, they were features of the work he’d never dreamed it was necessary to warn himself about when asked in the interview if he had any questions himself.

First, and probably foremost, George found the informatics infrastructure of the ERA most backward. At Goldman Sachs, he had been used to a high-performing mainframe computer with e-mail options. On his personal computer he already used Windows 3.0 and, even as a junior asset manager, he had received his first Motorola MicroTAC portable telephone some months back. Paper was certainly on the way out.

When beholding his section leader draft out a letter, by propelling his Waterman fountain pen across the paper with his chubby fingers, before calling the secretary by telephone for her to come and take it away for typing, George felt stuck in a time warp.

The following day, the explanation, given in all seriousness by the secretaries, that the best way of preparing a new draft regulation, to avoid suspicions from the delegates and save time typing, was literally to cut out paragraphs, with a pair of scissors, from a related legal text and, pot of glue in hand, paste the little pieces on a page of A4, left George bewildered. A last touch of Snowpake over the joints and a quick visit to the photocopier, to make the whole thing look half decent the job, “Le voilà!”. Astonishing.

If George had not passed such a pleasant time in his craft lessons at primary school in Chelmsford, and then learned to see that, in the context of the ERA in the 1990s, there was a certain down-to-earth pragmatism in what was being done, the primitive nature of things could well have blown George’s mind.

In any case, such was George’s inexperience that even were these everyday little things contributed the sense of uneasiness he felt in his first weeks at the ERA.

As it happened, maybe it was just as well that, after his encounter with Lundqvist, George ran next into Maxwell – or better put, Maxwell looked out George – a couple of weeks later.

Maxwell was to become one of George’s closest colleagues. His comments worked wonders at settling George’s jangled new-boy nerves while, at the same time, Maxwell found just the right way to alert George to the ultimate peril of the situation he had somehow put himself in.

Maxwell Oldale was a kind, rather soft-voiced Englishman from the Midlands. He was medium height and a little round in the middle, with auburn hair and a friendly smile. Most distinctly, Maxwell had an exceptionally refined sense of humour.

While George, throughout his career, never worked directly with Maxwell for any length of time, their paths often crossed at various working groups and at the annual ERA summer barbecue, held in the garden of the Director General each June. Maxwell was a seasoned financial controller and had seen just about every financial fiddle there was in the book.

Over the years, any conversation with Maxwell would leave George coming away, yet again, in admiration of his story telling abilities and, most importantly, his high command of irony.

“Don’t you see?” George would say to his colleagues, in reply to their questions of “How does Maxwell tell such funny stories? He always makes sure he is the butt of his own jokes. It’s masterly. Nobody feels insulted. The joke’s on him. That way everybody can find a space to laugh.”

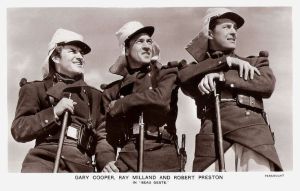

During that first encounter, Maxwell introduced George to what he called his Beau Geste theory of the functioning and purpose of the ERA.

“They say the ERA is the thinking man’s Foreign Legion,” said Maxwell in his finest satirical tone.

“Have you noticed?” he continued. “Nobody asks you too much about your past before you come in the ERA, provided you have a paper to prove it.”

Maxwell’s irony was coming over as sufficiently candid for George to know that Maxwell was telling him something truthful, while making sure George didn’t take the matter too seriously.

“You know how the Foreign Legion carries out special operations for the French Republic and then, if something goes wrong, the government denies all knowledge of them. Bit like that with us.”

Maxwell was treading a fine line between veneration towards, and mockery of, the ERA. George enjoyed such ambiguity. It reminded him of his own father, Sidney when he spoke about growing up in the East End and the fans’ comments about their beloved West Ham United football team.

“Some call it the main occupational hazard of working in the ERA,” Maxwell added. “The continual execution of the thankles task.”

Now it was George who was had the wry smile on his face, waiting for Maxwell’s further explanations.

“Just like in the film with Gary Cooper, with his brothers and that band of legionaries, under the scorching sun of the Sahara Desert. In the ERA we all come from all sorts of backgrounds, some are tough, some are meek, but we all fulfil a common mission.”

Maxwell made a gesture of brushing dust off his hands, to give the signal of ‘Job well done’.

“So just keep your rifle clean and your boots polished. Keep out of the way of any Sergeant Markoff types and wait for the next financial operation to be executed!”

Light as Maxwell had tried to make it, George took careful note of this warning, which immediately reminded him of the refrain from one of his favourite Status Quo songs, still fresh in his mind from the karaoke nights he had organised after hours during his time working at Goldman Sachs:

“You’ll be the hero of the neighbourhood

Nobody knows that you’re left for good

You’re in the army now

Oh, oh, you’re in the army – now

But little did George realise how useful Maxwell’s humour would be to him when he witnessed the most brutal “initiation ceremony,” which his older colleagues meted out a few weeks later, on a Greek colleague who had been part of the same intake to the ERA as George.

The name of the deserving victim was Nikos Papotis.