“Anybody against such an innovation would surely qualify themselves as a Luddite”, chimed George over coffee that morning, as a tricky discussion unfolded about the introduction of the new Artificial Intelligence tool for managing briefings in the European Regulatory Authority.

“But the briefing is the most critical work we do”, contested André. “I just don’t see how a machine can encapsulate all the elements of a Line-to-Take, to the same standard as any one of us would”, he insisted.

“That depends on what you mean by standards”, butted in Jernej, who until then had not participated in the group’s conversation. “The hierarchy seem to think more and more, as far as I can see, that the key indicator of a high standard briefing means getting the right font, the right line spacing and fitting it all into five pages”, he added, gesturing through his body language that he had little interest in pursuing any further the subject of this particular coffee-time debate.

André was evidently far more alarmed by the whole affair.

“In the end, it must mean fewer jobs for functionaries like us. And lower pay”, André asserted, with a sad shake of his head.

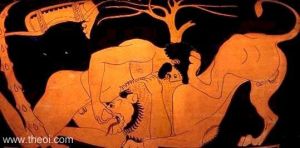

“That’s precisely what the Luddites said about the introduction of spinning machines!” interjected George. “The machines started replacing the cottage workers and their hand-held spinning wheels. The workers feared their jobs would disappear – and so they ransacked the machine rooms and burnt them to the ground!”

“That’s maybe, George,” replied Jernej. “But it still seems to me it was the computer that took over the functionary’s job, not the spinning machine”, he chirped, aroused now by the thought of a Luddite-style revolt against the slavish screen of his laptop.

“But I can assure you, Jernej”, continued George, “At least in my experience in the ERA, the efficiency gains from computers don’t necessarily mean fewer jobs for functionaries. Quite the contrary.”

George gathered his thoughts.

“Take the early 2000’s, as the start of informatisation in the ERA. Since then, not only do we work faster and produce more. We cover far more issues, from far more different angles, than we ever did. And the computer allows us to go into much more detail in the background analysis – no need to trip down to the library like we used to! Everything is so much quicker now!”

The others looked on while George continued. “If you look at the stats, you’ll see there are twice as many of us now as 20 years ago. Parkinson’s Law on the exponential growth of staff in administrations came true yet again!” he proclaimed, his forgivably pompous air prompting a couple of heads to knock back in amusement.

But Jernej was not satisfied with George’s optimism and couldn’t resist a repost.

“So, does that mean you’ve been reading Parkinson again, George? I don’t think we’ve heard you mention him since you last told us that ditty, how did it go, err? The work expands to fill the time available?”.

Jernej frowned, holding his finger and thumb to his chin in a gently mocking gesture. “I can’t see how Parkinson will help us when AI takes over. Our bosses will just give us even less time to do things and expect them to be done faster and faster.”

“I agree, cutting the time down to execute a task is a real risk,” replied George, “and I’m the first one to admit it seems everything in the ERA nowadays has to be done in the ‘right-here-and-now’. But if you consider that Parkinson also said that the work increases because officials make work for each other, then there’s more to Parkinson than meets the eye.”

George’s face showed a hesitant smile as he dwelt over the peculiar way artificial intelligence taking over the ERA was stirring reflection.

“In my 30 years in the ERA, with the number of tasks, and the detail and position that are now required, I reckon there has been at least a tenfold increase in what we produce!”

“Tenfold? Are you having us on again, George?” said André, with a slight screech of disbelief in his voice.

George was a little taken aback by André’s reaction. He thought he was well enough known in the ERA not to have his sincere comments taken as mockery. George decided to adjust the tone of his voice downward, in case his colleagues didn’t realize he was speaking in all seriousness.

“I’m sorry if it sounds like I’m exaggerating,” replied George. “But just imagine what it was like back-in-the-day to write by hand, or dictate to a shorthand secretary, all your correspondence; pass the manuscript to the typing pool; receive it back for checking; send it back if necessary for correction; receive it back again for signing or, if it was to go up the line, initialing and placing it in a transit folder to be passed from office to office. Oh, and before putting the original in an envelope and taking it down to the franking machine to register it before dispatching, don’t forget to pass by the Xerox machine, make a copy and put it in a ring file in the archive!”

André, Jernej and Konrad, the fresh, young intern, looked on, with a contrary mixture of humility and disdain on their faces.

“Any background research had to be done only after taking a walk of four flights of stairs to the library and searching through the dusty shelves for the right statistical yearbook or academic reference”, George insisted. “And Goodness Knows how much faster all our work is, now we have machine translation. That’s been a ‘véritable révolution’” he added in his best French accent.

He paused for dramatic effect.

“Those were the good old days! But how much fiscal policy do you think we actually got around to producing with the number of staff we had then?”

[to be continued]